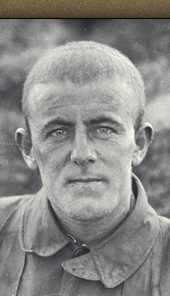

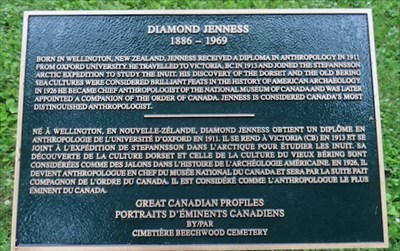

Father of Inuit Archaeology - DIAMOND JENNESS

DIAMOND JENNESS

Section 17, Lot 69 TG 1

Born in Wellington, New Zealand in 1886, Diamond Jenness was the second youngest son in a middle-class family of ten children. His father’s profession was that of a watchmaker/jeweler, though he also installed several clocks in municipal building towers in New Zealand. The family was encouraged to read, learn music, and engage in sports. Richling, in his biography “In Twilight and in Dawn,” writes that the young Jenness “was a proficient outdoorsman and an accomplished sharpshooter,” skills that helped prepare him for his experience in the arctic years later.

At an early age, Jenness showed proficiency for learning. He earned his first scholarship at the age of twelve by entering a composition competition for children under fourteen. In those days, in New Zealand, secondary education was only available to the wealthier families, so this scholarship enabled Jenness to complete high school and three years of college. He finished his final year of secondary education with six prizes: mathematics, science, Latin, French and English, and was named top student. He and sister May were the only two siblings to proceed on to college.

Jenness graduated from the University of New Zealand (from the constituent college then called Victoria University College) (B.A. 1907; M.A. 1908), receiving first class honors for both degrees. Then, when 22 years old, he received a scholarship that allowed him to pursue further education at Balliol College, University of Oxford (Diploma in Anthropology, 1910; M.A. 1916).

Field Work – Northern D’Entrecasteaux

From 1911 to 1912, as an Oxford Scholar, he studied a little-known group of people on the D'Entrecasteaux Islands in eastern Papua New Guinea. Jenness comments: "They peered at me from out-of-the-way corners, or through the doors of their huts, always at a safe distance.

Recalling a children’s [game] I had learned in one of the coast villages, I stooped down, tapped the ground with my fingers and chanted the refrain. The children drew nearer and nearer, and one or two with broad smiles began to imitate me. Then with a piece of string, I made some of their own cat’s cradle figures and held them out for their inspection. This turned the scale. Five minutes later a laughing crowd surrounded me…The natives could hardly believe that I was a white man, and kept asking my [guides] who I was, how I came to speak their language and where I had learned their game.”

Canadian Arctic Expedition

In 1913, Jenness was invited to join the government-funded Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE) that was led by two Arctic explorers - Vilhjalmur Stefansson and R.M. Anderson. He would be one of the two anthropologists on board; the other was Henri Beuchat. In June of that year, having barely recuperated from yellow fever contracted while in New Guinea, Jenness boarded the whaling vessel Karluk along with 12 other scientists.

The ship steamed up the British Columbia coastline towards Nome, Alaska, where they met up with Stefasson who had purchased two 60-foot schooners to assist in the expedition work. The three vessels then proceeded towards their rendezvous point, Herschel Island, just east of the mouth of the Mackenzie River, Northwest Territories.

The rendezvous never took place. On 12 August, the Karluk became locked in the sea ice. Stefansson, with his secretary McConnell, Jenness, Wilkins (later Sir Hubert Wilkins), and two Inuits, set out to procure meat for the crew. While they were ashore, the Karlak drifted westward to the East Siberian Sea, where it was eventually crushed in the ice off Wrangel Island. Thirteen of the crew perished on board, including Henri Beuchat.

With the ship gone, the hunting party set off on foot towards Barrow, Alaska (Utqiaġvik), 150 miles away, hoping to meet the two other vessels involved in the expedition: the Mary Sachs and Alaska. In Barrow, they learned that the two ships had anchored in Camden Bay, making it their winter base. Jenness remained behind and spent the first winter at Harrison Bay, Alaska, where he learned how to speak the Northern Inuit language, and compiled information about their customs and folklore. The next year, in 1914, assisted by interpreter Patsy Klengenberg (son of an Inuit woman and the trader Christian Klengenberg), Jenness commenced studying the Copper Inuit, sometimes called the Blond Inuits, in the Coronation Gulf area.

This group of people had had very little contact with Europeans, and Jenness, now the only anthropologist, was solely in charge of recording the aboriginal way of life in this area.

Jenness spent two years with the Copper Inuit people and lived as an adopted son of a hunter named Ikpukhuak and his shaman wife Higalik (name meaning Ice House). During that time he hunted and traveled with his "family," sharing both their festivities and their famine. By living with this Inuit family and partaking in their everyday experiences, Jenness did something that was "not often employed by other ethnologists" at the time: he lived with the people who were the subjects of his fieldwork. As Morrison in his “Arctic Hunters: The Inuit and Diamond Jenness” states: “His goal was to understand the Copper Inuit on their own terms, not in relation to some preconceived ‘ladder of creation’ with Europeans perched firmly at the top.”

Summarizing his first year with the Copper Inuit, Jenness wrote:

"By Isolating myself among the Inuit ... I had followed their wanderings day by day from autumn round to autumn. I had observed their reactions to every season, the disbanding of the tribes and their reassembling, the migrations from sea to land and from land to sea, the diversion from sealing to hunting, hunting to fishing, fishing to hunting, and then to sealing again. All these changes caused by their economic environment I had seen and studied; now, with a greater knowledge of the language, I could concentrate on other phases of their life and history."

As anthropologist de Laguna noted years later, his “accomplishments are the more remarkable when it is remembered that Jenness had to perform not only his own duties but [also] those of his unfortunate colleague, Beauchat.” Furthermore, Jenness's camera, anthropometric instruments, books, papers and even heavy winter clothing had all remained on board the ill-fated Karlak.

The CAE scientists kept daily diary logs, took extensive research notes, and collected samples which were shipped or brought back to Ottawa. Jenness collected a variety of ethnological materials from clothing and hunting tools to stories and games, and 137 wax phonographic cylinder song recordings he had made. (The latter’s musical transcription and analysis by Columbia University’s Hellen H. Roberts with Jenness’s word translations can be found in the monograph “Songs of the Copper Inuits” (1925). Eight of Jenness’s Copper Inuit recordings can be heard on CKUG’s website. The radio station is located in Kugluktuk, Nunavut, Canada. The website also features a short video demonstrating how Jenness recorded these songs with the technology available in 1913.)

Origin of the Copper Inuits and Their Copper Culture - In his article in Geographical Review, Jenness described how the Copper Inuit are more closely related to tribes of the east and southeast in comparison to western cultural groups, basing his conclusion on archaeological remains, materials used for housing, weapons, utensils, art, tattoos, customs, traditions, religion, and also linguistic patterns. He also considered how the dead are handled: whether they are covered by stone or wood, without any artifacts, as in the west, or “as in the east, laid out on the surface of the ground, unprotected but with replicas of their clothing and miniature implements placed beside them.”.

Jenness characterized the "Copper Inuits" as being in a pseudo-metal stage, in between the Stone and Iron Ages, because this cultural group treated copper as simply a malleable stone which is hammered into tools and weapons. He discussed whether the use of copper arose independently with different cultural groups or in one group and was then "borrowed" by others. Jenness goes on to explain that indigenous communities began to use copper first and following this, the Inuit adopted it. He cited the fact that slate was previously used among Inuit and was replaced by copper at a later time after the indigenous communities had begun to use it.

First World War

The scientific members of the Canadian Arctic Expedition completed their mission and left the north in 1916. Jenness was assigned an office in the Victoria Museum of Ottawa and instructed to write up his expedition findings. After six months of feverishly working on his collections, notes, and initial reports for the government, Jenness, concerned about the events in Europe, enlisted in the World War 1 and served in France and Belgium. Being of slight build and short of stature, he was assigned to duties other than direct combat.

Field Work and Writing

In December 1918, Jenness applied and received military leave to finish writing his Papau studies report in Oxford, (delayed due his having joined the CAE and then the war). While in Oxford, he received word that his unit was one of the first to be sent home from the war. Jenness returned to Ottawa in March, 1919, and the next month married his fiance, Eileen Bleakney. After their honeymoon in New Zealand, Jenness set about writing up his Arctic reports, and produced eight government reports in five volumes, totaling 1,368 pages.

Canadian First Nations

A year and a half after his return from the war, the Canadian Government made his employment at the Victoria Memorial Museum permanent, and he was assigned to study many of the First Nation tribes of Canada. (Jenness’s employment had previously been on a yearly contract basis.)

The Sarcee, on a reserve in Calgary, Alberta, were the first of many First Nation tribes in Jenness’s fieldwork. That experience also provided his first encounter with the deplorable conditions Canada’s indigenous peoples experienced on reserves. After the Sarcee, Jenness undertook a fieldwork study of the Sekani. Beothuk (extinct), Ojibwa, and Salish. Collins and Taylor refer to Jenness's Indians of Canada (1931c) as "the definitive work on the Canadian indigenous, dealing comprehensively with the ethnology and history of the Canadian Indigenous and Inuits".

Archaeological Discoveries

Although most of Jenness's time was devoted to Indigenous studies and administrative duties, he also identified two very important prehistoric Inuit cultures: the Dorset culture in Canada (in 1925) and the Old Bering Sea culture in Alaska (in 1926), for which he later was named "Father of Inuit Archaeology." These archaeological findings were fundamental in explaining migration patterns, and Jenness's views were thought to be "radical" at that time. Helmer states: “These theories are now widely accepted, having been vindicated by carbon-14 dating and subsequent field research.”

Administrative Duties

In 1926, Jenness succeeded Canada's first Chief Anthropologist, Dr. Edward Sapir, as Chief of Anthropology at the National Museum of Canada, a position he retained until his retirement in 1948. During the intervening years, although hampered by the Great Depression and World War II, he “strove passionately, but with mixed success, to improve the knowledge and welfare of Canada’s aboriginal peoples and to enhance the international reputation of the National Museum.”

Other administrative duties during this time include representing Canada at the Fourth Pacific Science Congress in 1929, and chairing the Anthropological Section of the First Pacific Science Congress in 1933. Jenness also served as Canada’s official delegate to the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences in Copenhagen, 1938.

Second World War and its aftermath

In 1941, eager to contribute to the war effort, he was seconded to the Royal Canadian Air Force, where he served until 1944 as civilian Deputy Director of Special Intelligence.

In 1944, he was made chief of the newly established Inter-Services Topographic Section (ISTS), the non-military section of the Canadian Department of National Defence (patterned after a similar Great Britain military intelligence organization, Inter-Services Topographic Department.) Jenness retained this position when, in 1947, the Canadian ISTS unit changed name (became the Geographic Bureau) and was placed under the Department of Mines and Resources.

From 1949 until his death in 1969, Jenness published more than two dozen writings, including the monographs: The Corn Goddess and other tales from Indian Canada (1956), Dawn in Arctic Alaska (1957) a popular account of the one year (1913 to 1914) he spent among the Inupiat of Northern Alaska, The Economics of Cypress (1962), and four scholarly reports on Inuit Administration in Alaska, Canada, Labrador, and Greenland, plus a fifth report providing an analysis and overview of the four government systems (published between 1962 and 1968 by the Arctic Institute of North America).

He was able to complete these writings due to an award from the Guggenheim Foundation to further “whatever scholarly purposes he deemed fit,” an award that amounted to more than two and half times his annual pension from the Canadian government. Diamond Jenness received many distinguished awards and honors in recognition of his contributions to his profession.

In 1953 Jenness was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1962, he was awarded the Massey Medal by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, and in 1968 he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada, Canada's highest honor. Between 1935 and 1968, he was awarded honorary doctorate degrees from the University of New Zealand, Waterloo University, University of Saskatchewan, Carleton University, and McGill University.

In 1973, the Canadian government designated him a Person of National Historic Significance and in the same year the Diamond Jenness Secondary School in Hay River was named after him. In 1978, the Canadian Government named the middle peninsula on the west coast of Victoria Island for him, and in 1998 Maclean’s magazine listed him as one of the 100 most important Canadians in history as well as third among the ten foremost Canadian scientists.

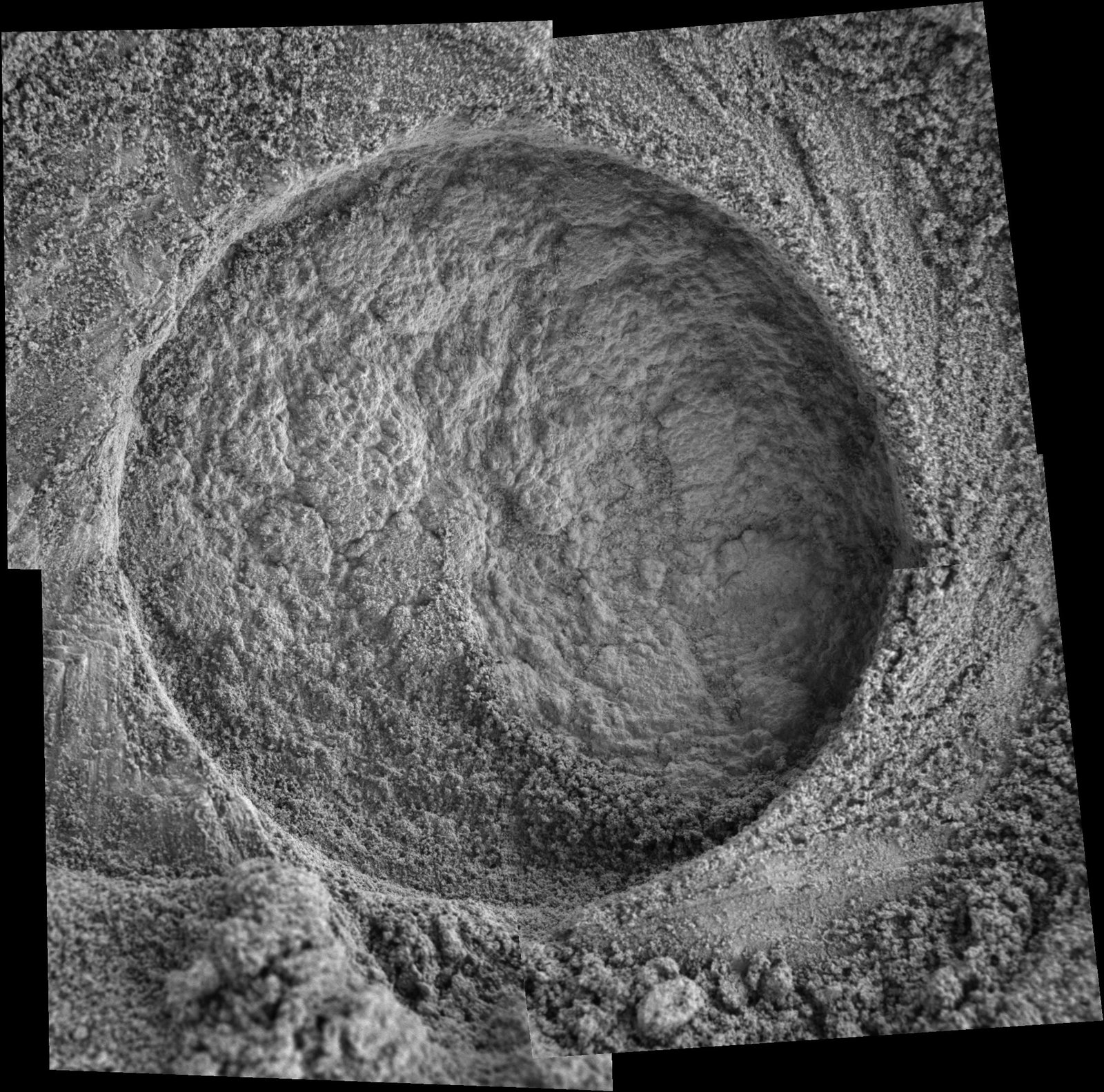

In 2004, his name was used for a rock examined by the Mars exploration rover Opportunity.